I like thrillers. Good thrillers. Not the slightly expanded movie scripts that they all seem to write now, but real novels that happen be exciting adventure stories. Like Alistair MacLean wrote. Through the sixties he did a string of excellent thrillers one after the other. He’s not read much now, but he should be.

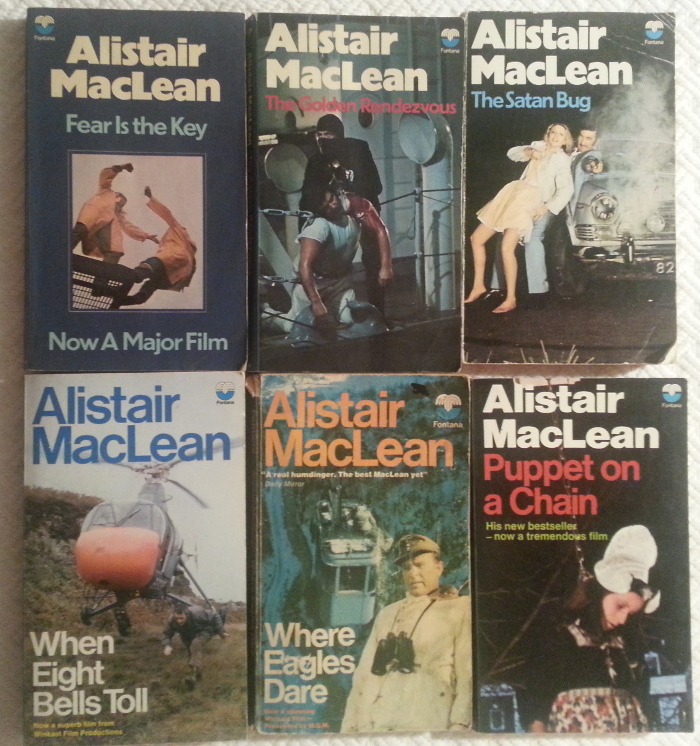

I think of his novels in these editions, Fontanas with photographic covers. No one makes covers like this any more.

I just reread The Golden Rendezvous (1962), one of his best and showing all his hallmarks, with a sailor on a luxury cruise ship getting caught up in a takeover of the ship by some very dangerous customers. The sailor is smart, fast-thinking, extremely competent, keeps his wits, and most importantly, like in all the best thrillers, he just doesn’t give up.

For me the key to a great thrilling novel or movie is a main character who isn’t particularly special in any way getting caught up in something and deciding to see it through to the end and not give up. (This is one of the reasons Children of Men is such a fine movie: the scene at the farmhouse where Clive Owen’s character realizes what he’s gotten into and that he has to save the pregnant woman. After that, there’s no going back and he never, ever stops.) The sailor here is a very good sailor, but he’s no super-spy. He’s a good sailor.

One of MacLean’s trademarks was keeping secrets from the reader, holding back information in order to reveal it either in an offhand way that makes you think back to what had to happen to set it up, or in a larger way where it’s revealed the narrator is not who you thought he was. I won’t give away examples of the latter, but there are a number of the former in The Golden Rendezvous.

For example, the sailor was hurt and is in sick bay with a few others. A chapter begins a few hours after the last one finished, and the sailor gets out of sick bay to do something on the ship without being seen. While he’s out a part of his plan is revealed to have been set up with one of the other injured sailors. There was no mention of this when we saw them both in sick bay, or when the sailor was narrating the beginnings of his plan; it’s only mentioned when that part of the action happens. Because, after all, shouldn’t we realize they would have been talking and plotting in the unrepresented time between chapters? MacLean doesn’t need to spell it all out like we’re fools. We need to keep our wits about us while reading, too.

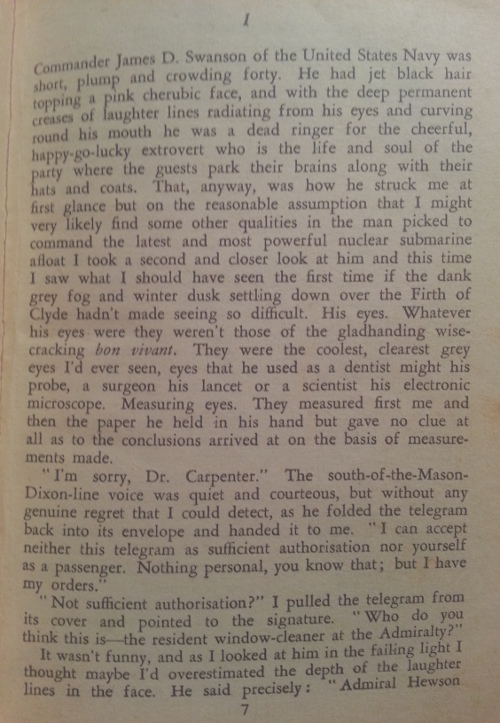

I’m struck by the density of the text, which is nothing like thrillers nowadays. Here is page one of my edition of Ice Station Zebra:

How would Dan Brown or James Patterson handle an opening like this?

Command James D. Swanson of the United States Navy was short, plump and crowding forty. He had jet black hair topping a cherubic face, and with the deep permanent crease of of laughter lines radiating from his eyes and curving round his mouth he was a dead ringer for the cheerful, happy-go-lucky extrovert who is the life and soul of the party where the guests park their brains long with their hats and coats. That, anyway, was how he struck me a first glance but on the reasonable assumption that I might very likely find some other qualities in the man picked to command the latest and most powerful nuclear submarine afloat I took a second and closer look at him and this time I saw what I should have seen the first time if the dank grey fog and and winter dusk settling down over the Firth of Clyde hadn’t made seeing so difficult. His eyes.

(A page or two later, the narrator is lying to Swanson about why he needs to be on his submarine and make a trip under the ice and break through high the Arctic … but we don’t know why.)

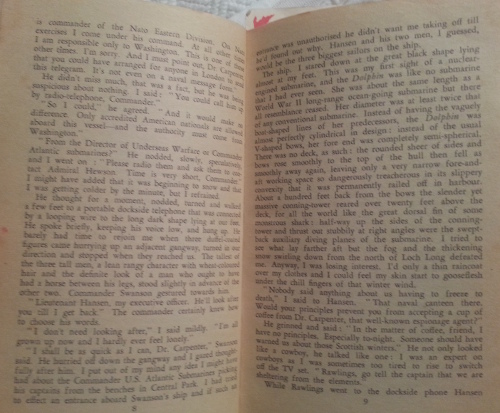

Look at that third sentence! Eighty-two words! Look at pages two and three:

Most of the thrillers I see in the stores now, not only is the reading level juvenile, every paragraph is two sentences long and every chapter is three pages long.

There was a good piece by J. Kingston Pierce in Kirkus Reviews last year: Fit to Thrill: Alistair MacLean Deserves to Be Read Again:

MacLean’s male protagonists were typically cool, morally resolute and prodigiously skilled, often harboring secret knowledge crucial to the plot’s resolution. The odds against them were predictably astronomical, and their physical and mental stamina might be sorely tested; but no matter the cruelty of their foes (Nazis, drug dealers, foreign agents, gun runners, etc.), MacLean’s heroes eventually prevailed. His female characters didn’t often enjoy such complexities of character. While they might display a flash of steel in their spines and barbs on their tongues, they were usually sexier than they were self-reliant—though not alluring enough to distract the leading men from their duties; unlike many of his contemporaries, MacLean believed that fictional love-making and romance were needless fetters on a story’s pace.

Ed Gorman knows writing, and he admires MacLean. He said in a recent blog post:

The 1970s was a great decade for adventure novels. There was a wave of writers, mostly British, who were writing suspense adventure—generally featuring a common man in very uncommon trouble—as well as the genre as ever been written. The most popular, and the most remembered, is Alistair MacLean, but there were others. Men named Desmond Bagley, Gavin Lyall and Jack Higgins. These writers were very nearly MacLean’s equal; if Mr MacLean’s early work is the measuring stick.

I agree about Bagley, Lyall and Higgins, and I’d add Hammond Innes to the list. Try them all, but start with MacLean, and look for an old Fontana paperback.

Miskatonic University Press

Miskatonic University Press