Last night I saw the new production of the Philip Glass/Robert Wilson (with Lucinda Childs) opera Einstein on the Beach. It was an astounding performance of an incredible work, and one of the best shows I’ve ever seen. It’s four hours and twenty minutes long—that’s 260 minutes—without any intermission, and though the audience can come and go as they please, most people stayed in their seats the entire time. I did. I didn’t want to miss any of it. It was enthralling and exciting and hypnotic and marvellous.

- Einstein on the Beach (Pomegranate Arts tour official page)

- Einstein on the Beach (Philip Glass official page)

- Einstein on the Beach (unofficial page with many notes)

When I came into the hall, about fifteen minutes early, it had already started.

That’s Kate Moran on the left and Helga Davis on the right. They sat there for a while, just like that, and then the chorus slowly began to walk into the orchestra pit, and then Moran and Davis began to talk. “Knee Play 1” had begun and the opera was underway. The two of them were in all of the “Knee Plays” (which serve as the introduction, intervals between acts, and conclusion), as well as in some of the acts. Both of them were excellent but Kate Moran stood out specially for her work in “Trial/Prison.”

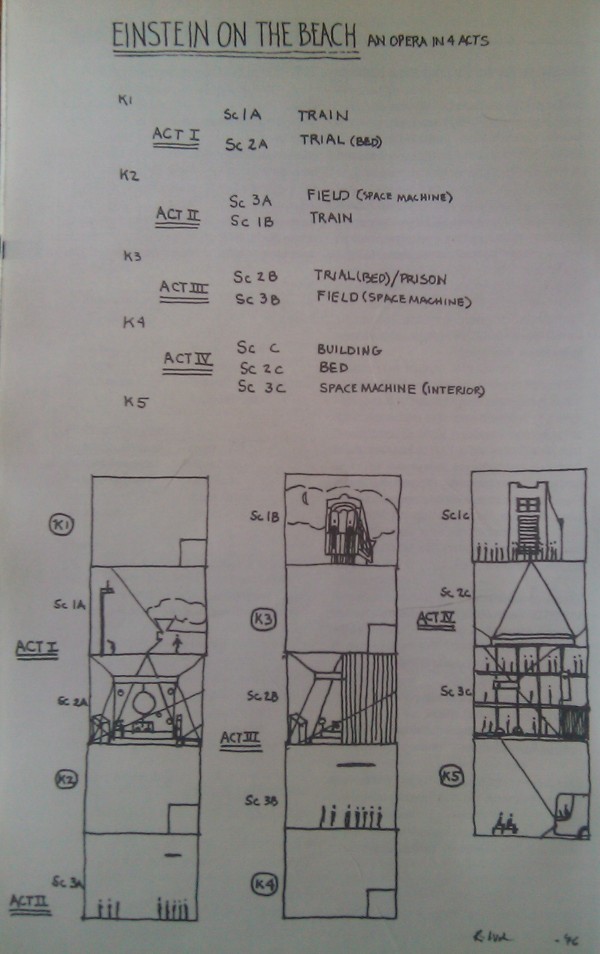

The program showed the original storyboard done by Robert Wilson, the director:

K1 there is “Knee Play 1.” The square in the bottom right is the white square behind the two in the picture I took.

There’s no story to the opera. Or perhaps there is. I don’t know. But what you see in the storyboard is, for some of the acts, all there is. In act two, “Train” (top of the middle column) we see two people at the back of a train. They slowly come out onto the back deck, then they go back in. The Philip Glass Ensemble and the choir are playing. It takes about twenty minutes. It’s repetitive. It’s wonderful.

There are two dances, choreographed by Lucinda Childs, that are glorious and energetic, with the eight dancers (four men and four women) coming together in various combinations, then breaking up and reforming new groups, running and twirling and leaping beautifully.

The final scene, “Spaceship,” I can hardly begin to describe. It follows “Bed,” which (in this production at least—I suspect it was different earlier) is ten minutes of a long bright white rectangle moving from horizontal to vertical and then ascending up to the top of the stage. The soprano sings a beautiful solo. I admit there were a few minute here where my interest flagged.

But then “Spaceship” began. The curtains pull back to show actors and the Ensemble on a three-storey structure at the back of the stage, the musicians playing and the actors doing something with the light display on the back wall that gets brighter and busier and more complex as the act goes on. A boy in a glass box comes up through a trap door and ascends to the top of the stage, then moves back down and up. A man in a glass box moves horizontally across the stage about twenty feet up. Two dancers wave lights around as if directing a ship in for a landing. A man flies across the stage a few times. The choir is singing. The band is playing. Then the curtain comes down, the music keeps playing, and a little toy rocket in a spotlight moves up from the floor, stage right, to the top, stage left. Then the curtains open again and we see it all again, with the lights and actors and musicians and flying people.

And then in the last “Knee Play” it’s back to Kate Doran and Helga Davis, plus a bus driver (whose bus is in the same spot as the white square at the start) who tells a touching story about two lovers in a park.

I’ll never forget it. If you have a chance to see it, go.

Further reading: Three relevant articles from The Economist:

Miskatonic University Press

Miskatonic University Press