Digital humanities librarian position at York University Libraries

York University Libraries, in Toronto, where I work, is looking for a Digital Humanities Librarian. From the job description:

In the twenty-first century, digital libraries are as essential to humanities scholarship as physical libraries have been in the past. Digital humanities is an evolving specialization in librarianship. The incumbent will work closely with researchers, students and other subject librarians and provide leadership in incorporating technologies into the research activities of the humanities community at York University. This librarian will work collaboratively to develop strategies and environments for disseminating library resources in support of humanities research; contribute to the processes of digital media production, practice, and analysis in the humanities; engage in scholarly communication initiatives; and liaise and collaborate with digital humanities researchers. The successful candidate will also participate in the development of the collection in an area(s) related to his or her academic background.

The successful candidate will participate in teaching, reference, collection and liaison activities in the Libraries and elsewhere on campus, and be proactive in developing new programs and services. The chosen candidate will play a role in the ongoing development of information literacy initiatives; participate in special projects, such as assessment, and the development of web-based resources; participate in collegial processes of the Reference Department; serve on committees of the Libraries and of the University; and contribute to librarianship by carrying out professional research and scholarly work. Some evening and weekend work is required.

It’s tenure-track, for people who’ve been out of library school up to five years. I’m not on this search commitee, so if you have any questions I might be able to answer.

I would love to work with a really good person in this job!

Business librarian position (tenure-track) open at York University

Update 1 March 2011: There was a typographical error in the original posting (it was advertised as an Associate Librarian, not Assistant) so it had to be reposted. The new deadline is 22 April 2011. I’m announcing it again in case you missed it the first time or didn’t apply because of the rank. If you applied the first time, you will have received an email about what to do.

We’re looking for a business librarian with special knowledge of finance to fill a position opened by retirement where I work, at York University in Toronto. It’s tenure-track, and open to people who’ve been out of library school for up to eight years. This new librarian’s office will be beside mine in the Schulich School of Business, which is one of the the top business schools in the world.

I’m on the search committee, so don’t ask me any questions beyond the basics, but get in touch with John Dupuis, head of the science library, if you want to know more about York and what it’s like here.

News about "How to Make a Faceted Classification and Put It On the Web"

I wrote How to Make a Faceted Classification and Put It On the Web for library school in 2003. I’m delighted that it’s still of interest, as a couple of recent things showed to my surprise.

First, the paper was translated into Dutch: Hoe maak je een facetclassificatie en hoe plaats je haar op het web? It was translated by the Information Architecture Institute. Many thanks to Janette Shew and the IA Institute’s Translations Initiative for doing this.

Second, How to Reuse a Faceted Classification and Put It On the Semantic Web, by Bene Rodriguez-Castro, Hugh Glaser and Les Carr (of the School of Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton), takes my example of dishwashing detergents and extends it in mind-boggling ways that I’m still grappling with as I learn about ontologies and RDF. Here’s the abstract:

There are ontology domain concepts that can be represented according to multiple alternative classification criteria. Current ontology modeling guidelines do not explicitly consider this aspect in the representation of such concepts. To assist with this issue, we examined a domain-specific simplified model for facet analysis used in Library Science. This model produces a Faceted Classification Scheme (FCS) which accounts for the multiple alternative classification criteria of the domain concept under scrutiny. A comparative analysis between a FCS and the Normalisation Ontology Design Pattern (ODP) indicates the existence of key similarities between the elements in the generic structure of both knowledge representation models. As a result, a mapping is identified that allows to transform a FCS into an OWL DL ontology applying the Normalisation ODP. Our contribution is illustrated with an existing FCS example in the domain of “Dishwashing Detergent” that benefits from the outcome of this study.

My advice to any library school students reading this: if you think a paper’s half-decent, post it online with a Creative Commons license. Good things may happen.

Best quote I've read this year

That Alexander was a military leader of genius is clear, but what of his character as a general? We are not privileged to know whether he, like the British commander Orde Wingate in Abyssinia (as it was before the Second World War), ever gave his officers their battle orders lying in his tent stark naked and smoothing his pubic hair with someone else’s toothbrush. Perhaps Macedonian generals did not use toothbrushes.

— Paul Cartledge, Alexander the Great: The Hunt for a New Past

How many librarians does it take to change a lightbulb?

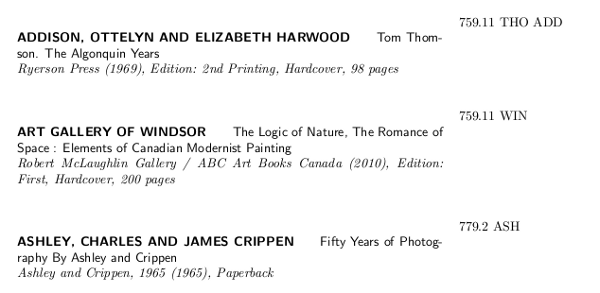

Nice-Looking Printed LibraryThing Catalogue

Last October I was at Access 2010, a conference about libraries and technology. Since 2002, the day before the conference begins there is a Hackfest. Last year it was organized by Dan Scott and Alex Homanchuk. They did a great job and we all had a lot of fun. It was a very productive Hackfest! I worked on something there that I’ve been meaning to write up for a while, and here it is.

I proposed a Nice-Looking Printed LibraryThing Catalogue: “It’s possible to export from LibraryThing in custom spreadsheet formats–but what if you want a nice-looking printed catalogue for a small special library? Use OpenOffice.org or LaTeX, with a scripting language, to generate an attractive printed catalogue.”

This was on my mind because I recently became the librarian at The Arts and Letters Club of Toronto. We have about 1700 books in the collection. Our collection policy centres on books by or about members, and then there are sections on Toronto and on clubs, and we have some general reference as well.

The catalogue I inherited was kept in Word and every now and then would be updated, printed out, and put in a binder on a table in the library. I’d like to make the catalogue searchable, and it would be easy enough to generate a PDF from the Word file and put that on our web site. People could do keyword searches in the PDF. That’s very basic, but it’s enough for basic author or title or keyword searches.

But I’d like to do more. The library uses an unusual classification system. There are several high-level categories, based around the LAMPS disciplines that are the fundamental basis of the Club: Literature, Architecture, Music, Painting, Stage. Along with them we have Reference, Toronto, Clubs, and Subjects Other Than LAMPS. Within each category books are sorted into two sections: by title and by author. This system does a good job of collocating items broadly by LAMPS discipline, but it means that books about A.Y. Jackson are scattered across the Painting shelves. Instead of being all together under his name, they are shelved either by title or by the author of the book.

One way to fix this would be to reclassify everything with the Dewey Decimal Classification. How would I get the Dewey numbers? One easy way would be to use LibraryThing to manage our collection. When one enters a book into LT, it often knows the Dewey number already, or it can find it. The numbers it doesn’t know I could look up in the Toronto Public Library’s catalogue. They have an excellent collection for Toronto-related things. I could add the Dewey number to the LibraryThing record for my own use and for everyone else’s.

Using LibraryThing as a catalogue would simplify a lot of things for me. But it would be overkill for what people in the library actually need. A simple printed catalogue is enough. How could I use LibraryThing to generate a nice-looking printed catalogue? Aha, I thought: a Hackfest project.

At the Hackfest three other people were interested in the idea: Ganga Dakshinamurti (who works at the University of Manitoba), Wendy Huot (Queen’s University), and Rebecca Larocque (North Bay Public Library). We sat at a small table in a reading room and started working. One or two other Hackfest groups were working in the room as well, along with a bunch of students who were either reading or sleeping or both.

For the quick view of what we did, look at the Hackfest report. Our bit (done by by Wendy and Rebecca) starts on page 14.

Rebecca, as the slides show, hacked up a way of exporting the data from LibraryThing and pulling it into OpenOffice where she pulled apart the metadata and put it back together in a new way on the page, making a nicely formatted catalogue entry for each book. She fitted the metadata to a template, sort of like a mail merge, where you have a bunch of addresses and print off many copies of the same letter, addressed to different people. Rebecca got all the way done except for one small thing: each entry in the catalogue ended up on a separate page! Instead of having twenty or thirty on the same page, OpenOffice wanted to do a fresh page for each. This presented a small problem for a library with 1700 books, but there must be some simple solution for it.

Having not the slightest clue how to do any of that, I stuck with my limited Ruby and LaTeX skills.

Both Rebecca and I were using LibraryThing’s export feature. (You will only see it on that page if you’re a LibraryThing user (it’s free — if you haven’t already tried it, do so) and you’re logged in. You can get your data out of LibraryThing in two formats: CSV and TSV labelled as Excel (again, those won’t work unless you’re logged in).

Rebecca used the TSV and I used the CSV. We were working away, discussing what they contained, when we realized they were slightly different. Here’s the order of the CSV:

- TITLE

- AUTHOR (first, last)

- AUTHOR (last, first)

- DATE

- LCC

- DDC

- ISBN

- PUBLICATION INFO

- COMMENTS

- RATING

- REVIEW

- ENTRY DATE

- COPIES

- SUBJECTS

- TAGS

And here’s TSV:

- book id

- title

- author (last, first)

- author (first, last)

- other authors

- publication

- date

- ISBNs

- series

- source

- language 1

- language 2

- original language

- LCC

- DDC

- BCID

- date entered

- date acquired

- date started

- date ended

- stars

- collections

- your tags

- review

- summary

- comments

- private comments

- your copies

- encoding

Knowing the LibraryThing book ID is extremely useful because then you can use all the LibraryThing APIs, including librarything.ck.getwork, which gets the “Common Knowledge” for a book. Unfortunately, I didn’t have it in the CSV. I asked Tim Spalding about this on Twitter and he said “APIs are a big problem. It’s very unclear what we’re allowed to do, so they’ve stagnated while we discuss the issue.” He liked the idea of the nice-looking printed catalogue, though, and said he might put someone on the job of making it a built-in feature. I hope that happens!

Enough about the data dumps. Rebecca was working with hers and I was working with mine. I used a Ruby CSV library to parse the CSV, and then I used ERB to build a LaTeX template. It looked like this:

<% items.sort_by{ |a| [ a[2], a[0].gsub(/^(The |A |An )/, '') ]}.each do |i| %>

<% ddc = i[5] || "" %>

<% title = coder.decode(i[0]).gsub(/&/, 'and') %>

<% author = coder.decode(i[2]).gsub(/&/, 'and') || "[unknown]" %>

<% publication_info = coder.decode(i[7]) .gsub(/&/, 'and') || "" %>

<% tags = coder.decode(i[15]).gsub(/&/, 'and').gsub(/,/, ', ') || "" %>

<% if author == lastauthor %>------------<% else %>\MakeUppercase{\textsf{\textbf{<%= author %>}}}<% end %>

\hspace{2em}\textsf{<%= title %>}

\newline

<% unless publication_info == "" %>\textit{\hspace{1em}<%= publication_info %>}\newline<% end %>

\hspace{1em}<% unless tags == "" %>\textsc{<%= tags %>}<% end %>

<% lastauthor = author %>

&

<%= ddc %> \\\

<% end %>

All the beauties of typesetting language and a scripting language combined into one.

All of that LaTeX business was to make the printed catalogue look the way Ganga and Wendy had designed. They spent the morning looking at examples of printed catalogues online and at what information we would want to include in one. In the afternoon Wendy was on her own, and she found more excellent examples, photographs and scans of beautiful old catalogues, and made a design for what ours should look like. The catalogues were absolutely gorgeous for their design and typography, and they contained much more information than we’d expected, especially, if I recall, in booksellers’ catalogues.

Unfortunately my LaTeX skills weren’t good enough to come near to these, but the basics are there, as you can see in this sample that contains a mishmash of various books (PDF). Here’s an example of the author listing:

After the books are listed by author there’s a classified listing where they are in Dewey Decimal order, the way they would be on the shelf.

I put all of the code on GitHub: nlpltc. There’s the Ruby script, the LaTeX template, and a sample CSV file. If you have Ruby and LaTeX installed then it should work on any CSV export from LibraryThing.

My hope is that this will inspire Tim Spalding and his team of book-loving programmers to build a feature like this into LibraryThing so that users can fiddle a few options and then generate their own Nice-Looking Printed LibraryThing Catalogue.

Thanks to Wendy, Rebecca, and Ganga for making the Hackfest so much fun.

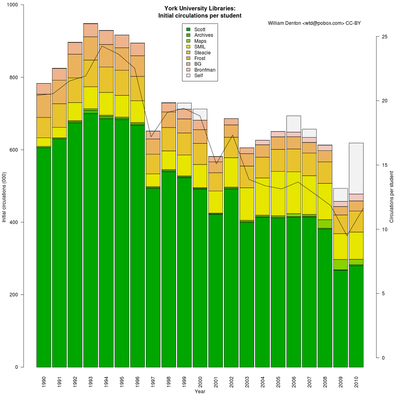

Initial circs per student

I’ve been learning R recently and did something that was mildly interesting so I thought I’d post about it.

I wanted to try graphing some data, so I needed some numbers. I remembered there were a lot of circulation statistics in the annual reports of York University Libraries, where I work, and that seemed like something interesting to look at. How is circulation changing over the years? I graphed ten years of circ data (we call it “circ” in the library world) and found that … it seemed to be staying about the same, at 600,000 initial circs per year. (Initial circulation means an item is being checked out for the first time. We count renewals separately. Initial circs + renewals = total circs.)

That was odd, I thought. But wait, the number of students at York has grown a lot over the last decade. In fact, from about 35,000 to over 50,000. What does that mean? I graphed initial circs per student, which showed the numbers on a steady decline. I got the numbers from the decade before and added them in, and the decline became even more obvious.

Here’s the chart (see also the full-size image):

Notice the three years (1997, 2001, 2009) where circulation drops sharply? Those were years there were strikes at York and teaching was interrupted (in 2009 for 88 days!). Peak circ was in 1993, peak circ per student in 1994, and after that things really started to change, with CD-ROMs and then the web. (See also Thom Hickey’s blog post Peak books.)

About our branches: Scott (the dark green) is by far the largest, covering arts, social sciences and humanities, and containing within it the Sound and Moving Image Library, Maps, and the Archives. Steacie is the science library, BG is the business and government documents library that closed in 2003, Bronfman is the business library that opened in 2003, and Frost the all-purpose library on a smaller second campus. The “self” number is for self-checkout, which is counted on its own though there are self-checkout machines in every branch.

I generated this with R and two data files. Here’s what I did. (If you know R then you’ll probably see lots of things I could have done better.) First, the two data files:

- York University Libraries circulation, 1990-2010 (taken from annual reports)

- York University enrolment, 1990-2010 (taken from the York University Factbook)

Notes about the data: the student enrolment numbers are for the November of the previous year. In the 1990s music and film were counted separately but I added those together into SMIL, the Sound and Moving Image Library, where they’ve been together for a long time. For the students I’m counting the total of all undergraduates and graduates, both full- and part-time. They behave differently but as long as I’m comparing the same thing year over year it’s a fairly reliable indicator, I think. I don’t include renewals in the figuring because renewing something doesn’t necessarily mean something the way that actually checking out an item does.

If you have R installed, and download those files, you should be able to run R at the command line and then copy and paste these lines in. You’ll see an image be created and then things get added to it bit by bit.

# Read in number of students and circulation per student

enrolment <- read.csv("york-enrolment-1990-2010.csv", header=T)

# Read in branch circ numbers, from annual reports

circ <- read.csv("york-circulation-1990-2010.csv", header=T)

# Set extra space on right-margin

par(xpd=T, mar=par()$mar+c(0,0,0,2))

# Stacked bar chart of circ numbers

# (Save the midpoints (which are the output of barplot) for use in

# x-axis labelling)

midpoints <- barplot(t(circ[2:10]), col=terrain.colors(9),

space=0.1, axes=F, ylab="Initial circulations (000)", xlab="Year",

main="York University Libraries:\nInitial circulations per student")

# Draw x-axis

axis(1, las=2, tick = F, labels=circ$Year, at = midpoints)

# Draw legend

legend("top", colnames(circ[2:10]), fill=terrain.colors(9), cex=1.0)

# Label the left-hand y-axis nicely at intervals

yat <- seq(0, 1000000, 200000)

axis(2, las=1, at = yat, labels = yat / 1000)

# Get ready to add a new plot to the same image

par(new=T)

# Line plot of circulation per student, setting y-axis limits

plot(circ$InitialCirc/enrolment$Total, type="l", xlab="", ylab="", axes=F, ylim=c(0, 25))

# Label the y-axis on right-hand side

axis(4, las=1)

# Add text to right-hand side

mtext("Circulations per student", 4, line=2)

# Clean up image margins (unncessary in a standalone script)

par(mar=c(5, 4, 4, 2) + 0.1)

text(18,26, "William Denton <wtd@pobox.com> CC-BY")

How are electronic resources (ebooks and articles) doing per student? I got two or three years of data and it was going up, but I ran into some problems graphing it nicely so I can’t show that. I didn’t think it was a long enough stretch of time, either. I’ll post about it if I get it working.

All comments welcome, including about how understandable this graph is.

(UPDATE 1 February 2011: I had two years of circ data (2004 and 2005) for Bronfman put under its predecessor BG. I corrected that in the data file and regenerated the graph.)

Poems to Memorize

Over the last year or more I’ve been memorizing poems, learning them by heart. It’s a lot of fun, far more than I ever guessed before I began. I put together Poems to Memorize as an EPUB ebook containing all the poems I know, and I’m making it available in case anyone else is interested. (Poems under copyright are listed by title, but the actual poems aren’t there. You can find them easily enough online.) I’ll keep it updated as I add to it. I use this as a quick reference on my Android phone when I’m learning a new poem or get stuck trying to recall an old one.

I began to memorize poems because I felt like my memory was going. Not because of age or dementia, but because I wasn’t spending enough time concentrating and focusing: too much of my time was taken up with short bursts and quick hits of information. I was reading less, what I was reading wasn’t as long as it had been, and I couldn’t remember the last time I’d sat on the sofa and read an entire book in one go. (Books like Rapt: Attention and the Focused Life by Winifred Gallagher (Globe and Mail review) and The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains by Nicholas Carr talk about all of this, and I recommend both.)

I decided to do something to work on my memory. I needed a challenge. I needed to test it. Why not learn some poetry off by heart? I’ve never forgotten a story my mother told me. She illustrates, and sometimes writes, children’s books. In 1993 she illustrated Realms of Gold: Myths and Legends from Around the World (written by Ann Pilling, and a fine book, though now out of print). Once she was out walking with a friend and mentioned that she was working on this book. When she heard mentioned the title, the friend launched into a recitation of a poem, doing the whole thing from heart. It was, I realized later, On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer, by John Keats:

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

(That’s a sonnet: fourteen lines, here structured ABBA ABBA CDCDCD. The Guardian published a history and analysis of the poem that explains the background of the poem, why Keats wrote it, and what it’s about.)

I was amazed: a few words jogged her memory and she was able to recite the entire poem! Imagine, having all that at your disposal! My mother’s friend was Scottish and had grown up there in the forties and fifties, with a very different education than I’d had. I’d never had to memorize a poem. I’d never had to read Keats. My knowledge of poetry was pitiful.

I decided I was finally going to learn this poem. It took about ten days.

My secret memorization technique? The shower. I printed it off, laminated the paper, and stuck it up in my shower. I started by repeating the first two lines, several times, until I thought I knew them. I’d repeat them through the day. The next day, I added two more lines. Then two more. Because it rhymed, it was easier than I’d thought, but it was non-trivial: I often had to check a copy I carried with me. But soon I had it all in my head.

Having the poem at my instant recall like that was an incredible experience. I could pull up a line or two whenever I needed it, to add a rhetorical flourish into my conversation. Knowing it so well I began to understand it more, to live with it, and the more it became a part of me, the more appreciation I had for it. It’s an astounding poem.

One by one I’ve learned more poems (and one song):

- To His Coy Mistress, by Andrew Marvell (1681)

- She Walks In Beauty, by Lord Byron (1814)

- Ozymandias, by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1818)

- Dover Beach, by Matthew Arnold (1867)

- Worldly Place, by Matthew Arnold (1867)

- Jabberwocky, by Lewis Carroll (1872)

- If, by Rudyard Kipling (1899)

- Solidarity Forever, by Ralph Chaplin (1915)

- The Second Coming, by William Butler Yeats (1919)

- Funeral Blues, by W.H. Auden (1938)

- A Subaltern’s Love Song, by John Betjeman (1941)

- A Study of Reading Habits, by Philip Larkin (1960)

- Party Politics, by Philip Larkin (1984)

“Dover Beach” was a tough one to learn. A character in Ian McEwan’s novel Saturday recites it from heart, which when I read the book seemed like an impossible task, but eventually I learned it. It was a joy when the last lines settled in place and the whole poem was mine. I was able to recite it, impromptu, standing on the shore of Lake Ontario at Niagara-on-the-Lake at midnight as the waves crashed in, the United States just across the river and Toronto’s lights shining in the distance. Knowing the poem made that night all the more powerful.

The Case for Memorizing Poetry, by Jim Holt, from The New York Times, tells a similar story to mine. He’s learned many more poems than I have so far. You should try it too! You probably already know some poems by heart, so you’re off to a head start. Pick a new one and learn it. It’s worth it.

Finally, a note about how I made the book. I began it by taking some other EPUB book and stripping out everything I didn’t need. I edit it by hand (with Emacs). These all helped me figure things out:

- Creating epub files, by Bob DuCharme

- .epub eBooks tutorial

- Build a digital book with EPUB by Liza Daly

- Threepress Consulting’s EPUB validator

If you unzip poems.epub you’ll see all the files but one. build.sh is what I use to regenerate the EPUB book:

#!/bin/sh # Turn the poems/ directory into an EPUB file rm -f poems.epub poems/*~ zip -Xr9D poems.epub mimetype META-INF/ poems/

Miskatonic University Press

Miskatonic University Press