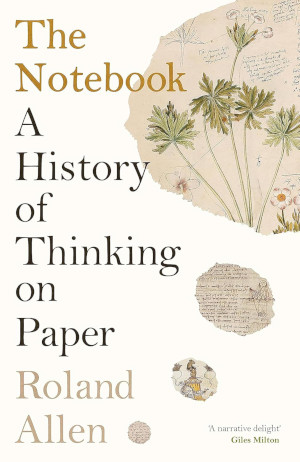

Over the summer I read The Notebook: A History of Thinking on Paper by Roland Allen, and I highly recommend it to anyone who regularly keeps notes, even if not on paper. I keep my work notes digitally (in Org), which is the best system for me in my work, but for everything else I use paper. Whatever your methods, The Notebook is full of interesting examples that will give you ideas about how you can keep your own notes. If you don’t use paper, it may convince you to try: there are many mental and memorial advantages to using paper over a screen, as Allen discusses.

This is a popular book, not a scholarly one, but it is well researched and will lead the curious reader on to many intriguing sources. Allen writes in a lively, engaging way. Aside from notebook users, anyone interested in stationery, documentation or the history of scholarship should also look at it, but it has wide appeal. (If you know someone is particular about their pens and pencils or where they write things down, this will be a great present for them—but make sure they don’t already have it, because many stationery lovers stay current.)

Allen takes a generally historical approach: Luca Pacioli and double-entry bookkeeping, Pisanello, Leonardo, Francis Bacon, through album amicorum and commonplace books, ship’s logs and police notebooks, on to Charles Darwin, Paul Valéry, Virginia Woolf, Agatha Christie, diaries kept by nurses documenting patients recovering, and much more. Each chapter is nicely self-contained and discusses some aspect of using portable books full of blank pages.

Reading this got me using a notebook again. Years ago I moved to notepads where I would jot down quick notes and ideas (I like Rhodia paper), or sheets of paper I would later file, but now I’m back to using a notebook and I wish I’d been using one all along. I’m documenting things, grappling with ideas and showing my work as I go, gluing in snippets from magazines, writing in quotes from books, doing sketches, and more. I’ve missed having a notebook at hand, and it’s a delight to flip through it whenever I want. It will be nice one day to have a whole shelf full I can review.

I tried out a few different notebooks (not a Moleskine, the artificiality of which Allen documents) and settled on a sketchbook from Above Ground Art Supplies here in Toronto. The size is right, the binding is sturdy, and the paper has a bit of tooth and can take not only fountains pen ink but light washes when sketching.

The Notebook is filled with examples, but it is not exhaustive. A review by Henry Hitchings in the TLS no. 6292 (03 November 2023) said:

Other maestros of the notebook who come to mind are Beethoven, Einstein, Thomas Edison and Antonio Gramsci—the last two of whom Allen doesn’t mention. His account never pretends to be comprehensive, and the emphasis is on groundbreaking uses of notebooks rather than on their most felicitous deployment, but I was struck by the absence of Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger, Franz Kafka and Jean-Paul Sartre, as well as Sylvia Plath, Geoffrey Madan, Katherine Mansfield, Northrop Frye and Samuel Beckett.

Hitchings mentions that Allen does not draw on the work of Matthew Daniel Eddy, who I will investigate, but there are many sources in the notes and bibliography that bear looking up. I read The Reckoning by Jacob Soll thanks to Allen, and will soon go on to The Information Master, about Jean-Baptiste Colbert.

The person I really missed was Harriet M. Welsch from Louise Fitzhugh’s classic children’s novel Harriet the Spy. Surely she did more than anyone else to get children to keep notebooks—and keep them private.

But Allen can’t include everything. What he does cover spans hundreds of years and is rich with interesting, rewarding and inspiring examples of how people have written things down.

Miskatonic University Press

Miskatonic University Press