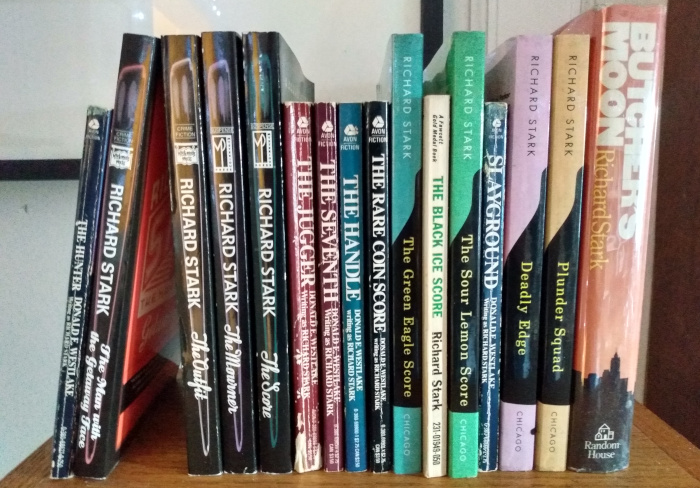

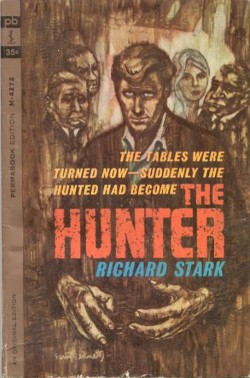

I just read the first set of Richard Stark books (that’s Donald E. Westlake writing under a pseudonym): the sixteen Parker novels and the four Grofields, published from The Hunter (1962) to Butcher’s Moon (1974). Twenty novels in a row, straight through. I’d read them all before, some two or three times, but never in consecutive publication order. Reading them scattershot, as I was able to find them used or they came back into print, I enjoyed each book on its own, but I completely missed the cumulative impact of reading them all together. Incredible! Those sixteen Parker books on a shelf are one of the finest sets of crime writing you could imagine. (There were eight more, published from 1997 to 2008; I’m saving them for next year.)

I had not realized how much they form one continuous narrative with the boring bits left out. Each book carries on from the next, skipping over when Parker’s on vacation or between jobs at his place with Claire, but I think that every job Parker does, we see. We follow him from heist to heist, problem to problem. The connections between Westlake and Anthony Powell became even clearer. In Powell’s twelve-book sequence A Dance to the Music of Time, long stretches of time are skipped over, details of jobs and daily life are ignored, and the focus is usually on particular events where many people come together; these are examined in great detail, then re-examined later. We might read about something, then skip ahead a year to the next thing that matters. The same happens in Westlake’s sixteen-book sequence. Parker never reflects on past events the way Nick Jenkins does, of course. Parker never reflects on anything.

(Powell is one of only three writers mentioned in the books, and he’s very unlike the other two. In one book a driver is reading a Travis McGee book while waiting, and in another two men in Parker’s crew discover they both like westerns and loved Brian Garfield’s Sliphammer.)

Reading the series consecutively makes the differences between the novels stand out. First lines, for example: the first eight books all begin with “When” and describe Parker doing something, then there are four with “Parker,” then in Deadly Edge (1971) (the rock concert heist) Parker isn’t even mentioned: “Up here, the music was just a throbbing under the feet, a distant pulse.”

Each novel has four parts: the set-up; the heist, ending with something going wrong; the third section, flashbacks, each chapter from a different person’s point of view; then Parker’s back and he gets his money. That’s how it goes for a while, but Stark changes things over time. It’s a surprise in The Green Eagle Score (1967) (the army base heist, where Stan Devers is introduced) when chapter one of section two begins:

“They’re going to do it,” Ellen said. “I know they’re going to do it now.”

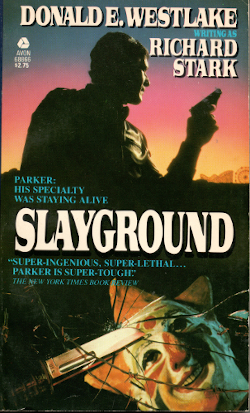

Sections three and four are back on Parker. It’s the same structure in Slayground (1971), but this time the heist goes wrong in the first chapter of the book, and Parker spends the whole book (covering about twenty-four hours) trapped in an amusement park that’s closed for the winter, with local gangsters after him and the $73,000 he has. He has a gun, but loses it in a fight. He still has his wits.

Here is a paragraph from chapter one of part four of Slayground. Parker is in the fly loft of a theatre while some gangsters are milling around below, some on stage, unsure of what to do. Parker has booby-trapped and rigged many of the buildings in the park, including the theatre. When the time is right, he drops everything that’s hanging above the stage down onto it and the men.

Parker raced along the catwalk, kicking off the iron weights, and yanking the slipknots on the ropes. He didn’t know if anyone was directly under the catwalk or not, but if they were, a twenty-pound weight dropping on their heads would put them out of action for a while. In any case, there were three or four of them standing around onstage, and the backdrops with their weighted bottoms to keep them straight weighed hundreds of pounds, and they were dropping toward the stage like guillotines, one after the other, from the front to the rear, slicing through the air with loud shushes, the weighted bottoms crashing on to the stage, the drops continuing to fall, the canvas piling up like starched laundry, finally the metal pipes, as long as the stage was wide and very heavy, thudding down, the ropes whistling through the pulleys under the theater roof, the rope ends released from the weight cages over the catwalk, the ropes pulling completely through and falling to the stage like dead brown snakes. And under them all, there would have to be a couple of bodies.

What a beautiful sentence there, describing everything falling and landing all in one long run, the language evoking the action, poetic but not showy. Many writers think that to make a scene fast and exciting it should be done in short one-sentence paragraphs. That’s almost always wrong. Stark knows how to use a long sentence for maximum action.

Plunder Squad (1972), the penultimate book, has the four sections, but the structure mirrors the earlier Grofield novel Lemons Never Lie (1971), where Stark used a triple-bounce plot. Grofield had three encounters with the same hood, the first small, the second medium, the third the biggest and very violent. In Plunder Squad there are three planned or attempted heists, and nothing works out. The main heist (art being transported between galleries) gets pulled without any major problems, but swapping the paintings for money goes bad.

The beginning of chapter one of the second section of Plunder Squad has Parker casing the gallery where the art is hanging. Parker doesn’t care about art, except for how much it could be worth if stolen. Stark offers no authorial commentary—he never does—but this flat description of two pop assemblages is brilliant.

Parker stood looking at the painting. It was four feet high and five feet wide, a slightly blurred black-and-white blowup of a news photograph showing a very bad automobile accident, all smashed parts and twisted metal. A body could obscurely be seen trapped inside the car, held there by jagged pieces of metal and glass. Superimposed here and there on the photograph were small comic-book figures in comic-book colors, masked heroes in bright costumes, all in running positions, with raised knees and clenched fists and straining shoulders and set jaws. There were perhaps a dozen of the small figures running this way and that over the surface of the photograph, like tropical birds on a dead bush. The painting was titled “Violence.”

Parker turned his attention to the mimeographed sheet he’d been given at the door. “Violence” had been loaned to the exhibit by Mr. and Mrs. Gerald Shakauer of Perth Amboy, New Jersey, who had purchased it in 1966 for thirty-five thousand dollars.

Parker moved on to the next painting. Hexagonally shaped, three feet in diameter, it was an exact replica of a red-background white-lettering STOP sign, with plastic sculptured noses glued onto it all over. This one was titled “Thanacleon IV.” Parker looked at the mimeographed sheet again: painted by, loaned by, purchased in 1968 for eighteen thousand dollars.

He moved on. There were twenty-one paintings in the exhibit, mounted on the white walls and on a temporary divider down the middle of the room. Adding up the numbers on the mimeographed sheet, a total of three hundred seventy-five thousand dollars had been paid out at one time or another in the last eight years for these paintings.

Speaking of the Grofield novels, Lemons Never Lie is the only one I’ll reread again. The first three (The Damsel (1967), The Dame (1969), and The Blackbird (1969)) read like Donald Westlake novels, part Dortmunder and part spy thriller. Lemons Never Lie is true Stark.

Nevertheless, Grofield is always a great character in the Parker novels, quoting Shakespeare and being a loquacious contrast to Parker, and he joins up again with Parker in the last novel of the original sixteen, Butcher’s Moon (1974).

Butcher’s Moon is one of the best crime novels I’ve ever read, but it needs to be read with the earlier ones in mind. Somehow all I remembered about it is this is where Parker goes back to get the money he had to leave at the amusement park in Slayground. I didn’t remember how good it is, and it’s damned good. It’s the culmination of everything in the previous books, and it blows up patterns and expectations. Most obviously, there are no sections, it’s fifty-five consecutive chapters.

Parker wants his money, the $73,000 (worth about $425,000 now). It’s not at the park. He figures the local mob boss, Lozini, has it. Lozini doesn’t. Parker still wants his money. He really wants his money. That’s all he wants. But he and Grofield get mixed up in city politics and a coup among the gangsters (the setting is reminiscent of Ross Thomas’s The Fools in Town Are On Our Side), and he doesn’t like it. Things go bad, and Parker calls in a dozen men he’s worked with on heists before, who we’ve met in the previous books including The Score (1964) (the Copper Canyon job a decade ago): Handy McKay (long retired, but who needs money because his diner in Presque Isle, Maine, is failing), Stan Devers, Dan Wycza, Ed Mackey, Philly Webb, Nick Dalesia, others; they all come in fast when Parker tells them there are big hauls to be had.

At the end of the book Parker isn’t his normal self: he helps someone. He goes to get someone out of of trouble. But it works in this book. Being caught up with these gangsters jockeying for power is so frustrating he loses his cool for the first time. Handy Mckay remarks on it: “That’s not like you.” And Parker wants revenge, which he’s never wanted before. He always just wanted the money and to get away clean. He says:

“I don’t care. I don’t care if it’s like me or not. These people nailed my foot to the floor, I’m going around in circles, I’m not getting anywhere. When was it like me to take lumps and just walk away? I’d like to burn this city to the ground, I’d like to empty it right down to the basements. And I don’t want to talk about it any more, I want to do it. You’re in, Handy, or you’re out. I told you the setup, I told you what I want, I told you what you’ll get for it. Give me a yes or no.”

“Parker, I was never anything but in, you know that,” says Handy. They’re all in. They have a joyous night of hold-ups and heists, then go to war with the local mob.

Parker seemed to maybe help someone in The Jugger (1965), but on rereading I see he didn’t, so it works. He was worried his cover identity would be blown, and he had to investigate. The one time when Parker doesn’t act like Parker is in The Black Ice Score (1968) (the African diamonds heist): in the last section Parker speaks at length and asks people to help him! Parker doesn’t ask for help, not like that. That moment is the one mistake in the books.

What Parker does at the end of Butcher’s Moon does work. Parker’s angry, he’s lost his cool, and when Parker loses his cool, you should walk outside, get in a car, start driving, and don’t stop until next Thursday. We’ve never seen this before, but we’ve never had a Parker book like this before. He doesn’t ask for aid and generosity, he assembles a big crew to do something that needs to be done, and they all get paid well for it.

After all of that, where could Stark go? I see why he waited almost 25 years to do another Parker book. I’ll be back at them in 2023, fate willing.

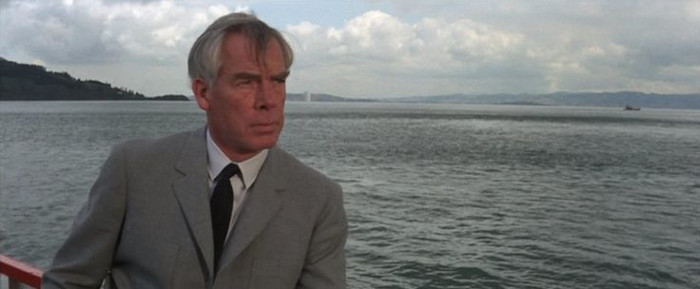

Until then I’m looking forward to Call Me a Cab from Hard Case next month. I’ll rewatch Point Blank, with Lee Marvin perfectly cast as Parker. And I saw on The Violent World of Parker that a French film of The Score, Mise à sac (1967) is on YouTube, with subtitles.

Miskatonic University Press

Miskatonic University Press