This month I got books on two of my favourite bands: Hawkwind and Rush.

Having been a male Canadian science fiction- and fantasy-reading teenager in the early ’80s, loving Rush can be taken for granted. I can’t remember exactly when I first heard about Hawkwind, but it would have been through their connection with Michael Moorcock. In university I picked up a double LP best-of, I think The Hawkwind Collection, which was a great introduction. I didn’t know anyone else who liked Hawkwind, and when I played them some, that usually didn’t change their opinion, but the fact Lemmy had been kicked out of the band, which led him to form Motörhead, gave it some notability, if not credibility.

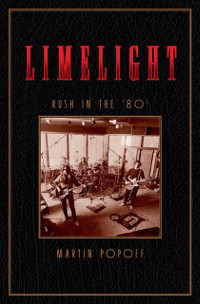

Canadian rock historian and critic Martin Popoff just released his second of three detailed books about Rush: Limelight: Rush in the ’80s, which follows Anthem: Rush in the ’70s. They’re thorough and very well documented, with lengthy quotes from the band members and others, covering all aspects of the history of the band, how they wrote the songs, their changing instrumentation and approach, and much else. The personalities of Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart all come across well, including the familiar dynamic of Geddy and Alex as the ones that are out in public while Neil is off on his own.

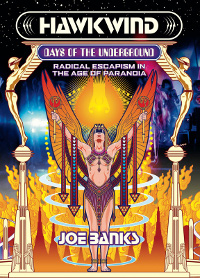

The other is Hawkwind: Days of the Underground; Radical Escapism in the Age Of Paranoia by Joe Banks, which looks equally thorough to the combined three Popoff books, but goes much more into the band’s place in culture. The Wire published an extract that gives a sense of it, and Banks had Acid, nudity and sci-fi nightmares: why Hawkwind were the radicals of 1970s rock in the Guardian recently.

This is Hawkwind in all their scuzzy, interstellar glory, the underground’s biggest band promoting their new single – less than a year later, and with a million copies of it sold, they’ll be headlining Wembley. It tends to be forgotten just how big this band of west London renegades were in the 1970s, playing to audiences of thousands wherever they went. They’re misremembered now, and were often misrepresented at the time, but as I discovered when writing a book about them, Hawkwind’s story amounts to an alternative narrative for 70s music culture – very different to the one that’s lazily trotted out by scene historians….

With their mood of anarchic possibility, Hawkwind gigs were a breeding ground for young punks everywhere, those “dedicated teenagers” coming of age and striking out on their own. John Lydon was a regular presence at their gigs in the early 70s, and was taken under Calvert’s wing at the height of Sex Pistols mania, with the self-proclaimed antichrist attending the singer’s wedding reception. Coming out of the same Ladbroke Grove milieu, Joe Strummer and Mick Jones of the Clash had grown up in Hawkwind’s world, while Brian James and Captain Sensible of the Damned were also fans.

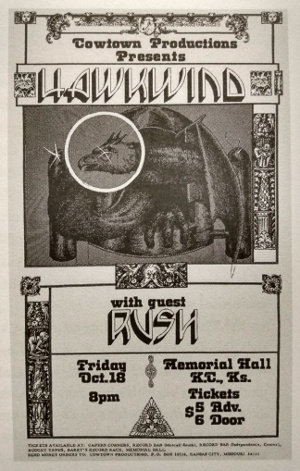

I was delighted to see this poster in the Hawkwind book: Rush opened for Hawkwind in Kansas City, KC on 18 October 1974! Hawkwind were touring for Hall of the Mountain Grill (it was on this tour that they had their equipment impounded by the IRS for an unpaid tax bill from their previous tour). Rush was on their first American tour, supporting all kinds of acts, with Neil Peart having just replaced first drummer John Rutsey—this was before Fly By Night. Popoff mentions the connection in Anthem: “Following the band’s dates with Kiss, plus assorted shows with the likes of Hawkwind and T. Rex, Rush did a clutch of Ontario dates with Scottish hard rockers Nazareth—a band that would take them across Canada the following year.”

I always feel obliged to mention indexes in reviews of nonfiction. Popoff’s books don’t have them, but they should. Banks’s Hawkwind book does have an index, with one entry for Rush (the poster was not indexed), in a footnote in the chapter “New Worlds and Dangerous Vision: Hawkwind as the Ultimate Science Fiction Band:”

Bands including Van Der Graaf Generator, Genesis, Ramases, Black Sabbath and Rush also leaned in an SF direction, while the pop charts featured such songs as the Carpenters’ Klaatu cover ‘Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft’ and Sarah Brightman & Hot Gossip’s ‘I Lost My Heart to a Starship Trooper,’ the latter inspired by Star Wars and perhaps the best known song from the late 70s sci-fi disco boom (risqué lyrics include ‘Take me, make me feel the Force’—plus a reference to 1977’s other big SF film: ‘What my body needs is close encounters three’).

Popoff gives a chapter to each Rush album from the eighties, and I’m enjoying listening to each one as I read the chapter about it. It’s a perfect match. I’m looking forward to working through Hawkwind’s catalogue when I get to the Banks book.

Miskatonic University Press

Miskatonic University Press