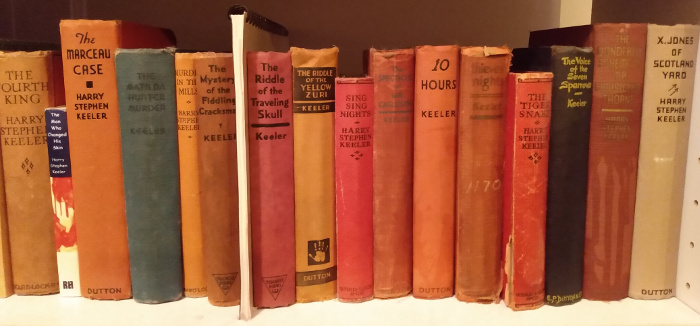

Harry Stephen Keeler is a forgotten American mystery writer. I can’t remember how I discovered him, but I began to read his stuff in the 1990s, and I joined the Harry Stephen Keeler Society, which because the web has changed is now much more quiet than it used to be, but Richard Polt has done marvellous work on raising Keeler’s profile. Getting the newsletter in the mail was a treat.

A couple of weeks ago I got a copy of The Portrait of Jirjohn Cobb (1940) at the library. I’d heard about it, but never read it. Here’s how Polt summarizes it:

The direct action of The Portrait of Jirjohn Cobb (1940), which has to be one of the most astoundingly unreadable novels ever written, consists of four characters, two of whom sport outrageous accents, sitting on an island in the middle of a river, talking and listening to a radio, again for hundreds of pages. And these novels were only the first volumes of two multi-novel sequences! What do these people talk about? Well, it would really take hundreds of pages to explain. These works are the Waiting for Godot of the Keeler canon, drawn out to the length of Finnegans Wake.

The Portrait of Jirjohn Cobb is, I agree, essentially unreadable. Anyone who has never read a Keeler novel before would become more amazed and appalled page by page but soon throw it away and ask whoever gave it to them what the heck they were thinking. But someone who has read a Keeler novel … well, it’s perfect Keeler, with outrageous accents, no action, and endless detailed explanations about trivial plot points. And for that, it’s remarkably enjoyable. I liked it.

I especially liked it because the solution of the “mystery” (such as it is) ends up depending on how long someone looks at a particular work of art. Somewhere around page 250 we learn who Jirjohn Cobb is—the father of the grandfather of one of the men on the island—and some details of the grandfather’s will.

“And to each of my living nieces and nephews—10 in number—I bequeath a full hour of silent contemplation of, and in the company of, that remarkable man, Jirjohn Cobb, who created me, and through my brothers and sisters in turn, them. For was it not Velasquez who said that a still-life should be studied for never less than 20 minutes?—a landscape for never less than 40?—but a portrait for never less than 60?”

I’ve looked at a couple of books about Diego Velázquez but haven’t found any such advice.

In the novel, the man relating this part of the story—Abner Hick—spends six pages looking at his grandfather’s portrait of his (the grandfather’s) father. Then the candle that provides the only light in the room—the reasons for which have been explained in great detail—starts flickering and sputtering, and it turns out that it’s burned long enough that the wax has melted away to reveal a small metal cylinder hidden inside. And inside that is a document written in “minitype” that gives directions to a treasure worth $25,000. The painter wanted the money to go to one of his relatives who would spend a long time looking at his painting of his father, and this was how he arranged it.

Miskatonic University Press

Miskatonic University Press