Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 readymade sculpture Fountain is the most important work of art of the twentieth century. The Wikipedia entry on it sets out what it was (a urinal) and the history of the piece and its impact.

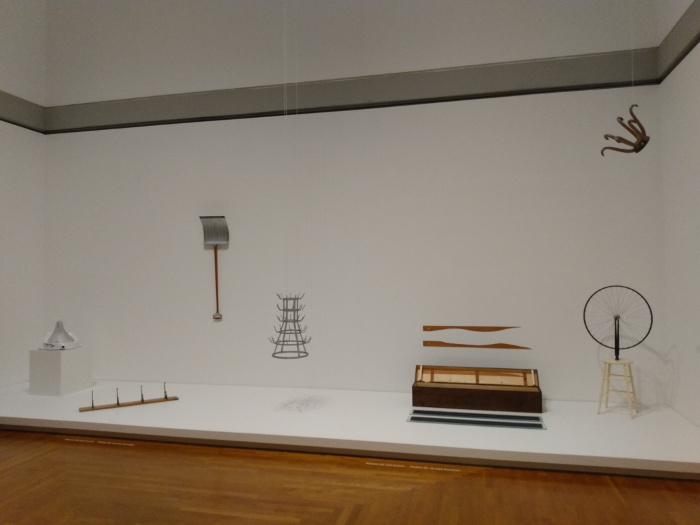

The National Gallery of Canada has a very nice collection of Duchamp pieces (remakes done in the 1960s), as show in the photo below. Fountain is furthest to the left. You can hear it in Listening to Art 06.02 The shovel on the wall is In Advance of the Broken Arm. You can hear it in Listening to Art 01.01 and Listening to Art 04.12. (There are recordings of other version of these pieces, too; check the artist index for links.)

Fountain is over a century old, but it’s still relevant. Take the banana on the wall that sold for $120,000 at Art Basel in Miami, which someone (not the buyer) then ate. Jonathan Jones’s Guardian piece Don’t Make Fun of the $120,000 Banana – It’s In On the Joke explains it:

Enter Comedian. That is the title of the artwork by Maurizio Cattelan, renowned for his stolen gold toilet, that has taken this sophisticated trade fair out of in-crowdy art websites and into mainstream news. Cattelan’s Comedian is a banana taped to a wall. Descriptions tend to carefully specify that it is fixed there with grey duct tape. Everyone stresses this somewhat bare technical fact, as if to find physical evidence that it really is, after all, art. At the weekend, after Comedian had already sold for $120,000, an artist named David Datuna joined the queue of fair-goers eager to take selfies with Comedian, but instead peeled back the grey duct tape, removed the banana from the wall and ate it.

Later:

Cattelan is acting out the tragicomedy of the contemporary artist. When Marcel Duchamp chose “readymades” such as a urinal or snow shovel, no one thought they had financial value – most were thrown away without a thought. Today’s museum versions were recreated long after the fact, when Duchamp became a hero to the conceptual art movement in the 1960s.

“Pop culture” columnist Vinay Menon in the Toronto Star took a different approach. In A $120K Banana Duct-Taped to a Gallery Wall Is Not Art — It’s a Scam he writes:

And I love all of these experts who shuffled out this week to defend “Comedian,” as if it were a momentous contribution to civilization. All these snooty nerds rambling on about how the banana represents the perishable nature or existence or how the banana is a metaphor for the patriarchy or how a banana suspended at eye level is a stark reminder of climate change and our dwindling food supply.

No, it isn’t. It’s just a banana duct-taped to a wall!

The day after that, the Guardian ran ‘It Is Something Deeper’: David Datuna on Why He Ate the $120,000 Banana , with Jordon Hoffman interviewing Datuna about his performance “Hungry Artist.”

Datuna: What I don’t like, however, is that a banana costs 20 cents. I think it is a good idea to put it in a museum if it is free to watch. But when you sell it for $120,000? Then decide to make a second and third edition, and that third edition is $150,000? It is silly, and not good for our contemporary life.

I have travelled in 67 countries around the world in the last three years, and I see how people live. Millions are dying without food. Then he puts three bananas on the wall for half a million dollars?

Hoffman: So you felt compelled to do something?

Datuna: Cattelan beat Andy Warhol. Maybe I shouldn’t say beat, but brought it to another level. I began to think: “What can I do with this banana? How can I bring it to yet another level?” And how to do it also with comedy? So I ate the banana. It is something deeper.

None of that would have happened without Duchamp.

Meanwhile, there’s a controversy about some recent claims that it wasn’t Duchamp that made Fountain, it was Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. I first heard about this in another Guardian piece, A Woman in the Men’s Room: When Will the Art World Recognise the Real Artist Behind Duchamp’s Fountain? by Siri Hustvedt, who had the baroness as a character in a novel. Dawn Ades responded the next day with Duchamp’s Fountain and the Feminist Avant Garde in New York:

The subheading on Siri Hustvedt’s article (A woman in the men’s room, Review, 30 March) says: “Evidence suggests the famous urinal Fountain, attributed to Marcel Duchamp, was actually found and signed by a forgotten female poet and artist? Why won’t the art world accept it?”

The art world doesn’t accept it because the argument is based on a number of false premises.

Ades did the introduction for Atlas Press’s Three New York Dadas and The Blindman, which has original texts very relevant to this issue (and the edition is a lovely well-designed book). She and Alistair Brotchie have written about Fountain and its creation in The Burlington Magazine (December 2019), and Atlas has put that article up on their site: Marcel Duchamp Was Not a Thief. It references “Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’: the Baroness theory debunked” by Bradley Bailey, which appeared in the October issue of the magazine.

The idea of Duchamp as an ‘art-thief’ has become something of an internet meme – accepted as true, without anyone ever bothering to check the evidence. Refuting it then becomes a matter of proving a negative, which is much harder to do. We are well aware that facts and evidence can be rather less amusing than speculation and conspiracy theories, but there is a truth to be revealed here that relates to the integrity of one of the most important artists of the last century. This truth has been carefully obscured by a blizzard of irrelevant research, the intention of which appears to have been to conceal the fact that no evidence whatsoever has been presented that links the Baroness to Fountain. However, Bradley Bailey’s recent article in The Burlington Magazine published evidence that finally puts paid to the speculative contentions of Spalding and Thompson. These contentions nonetheless need to be dealt with, and following Bailey’s article we wanted to summarise the facts of this affair.

They conclude with strong language:

Despite Gammel’s welcome aim of restoring agency to women artists and poets, it is unfortunate that she chose to champion the Baroness rather than the other women in the New York avant-garde who were actually involved in the 1917 Fountain incident, and who are no less forgotten by history: Louise Norton and Beatrice Wood. Contrary to Gammel’s approach, Spalding and Thompson have been belligerently abusive from the start. So we repeat what we wrote at the beginning of this letter: there is no evidence of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven being involved in any way whatsoever with Fountain. Unless they can provide evidence on this specific point, we suggest that the honourable course of action on their part would be to admit they were mistaken and to apologise for their accusations, which have turned out to be unfounded.

Miskatonic University Press

Miskatonic University Press