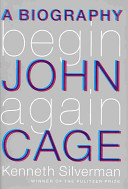

I just finished Begin Again: A Biography of John Cage, by Kenneth Silverman, which is a fine account of the amazing entirety of John Cage’s incredible life. I agree with John Adams’s review where he says, “Silverman is concerned less with parsing Cage’s aesthetics than he is with carefully recounting the life, which he does in a matter-of-fact, occasionally plodding manner,” but also where he says, “Cage himself is revealed in a richly shaded and profoundly human portrait” and that the book shows “Cage’s enormous capacity for work, together with his exceptional self-discipline as an artist (something learned from Schoenberg) and his willingness to approach every new challenge with a ‘beginner’s mind.’ For this alone it is a book worthy of being read by anyone, young or old, who is faced with the daunting task of a new creative beginning.”

Every page is filled with remarkable details and incidents, like p. 41 for this in late 1940 when Cage is raising money for his Center for Experimental Music:

He played some of his percussion records for the artist Diego Rivera, who became “very enthusiastic,” Cage said; Rivera spoke to influential people on behalf of the Experimental Center and “referred” him to Charlie Chaplin.

These two names appear out of nowhere. However, two pages later we read, “He learned that people of Chaplin’s celebrity were ‘very difficult to get to.’” No doubt! Still, pretty good for a 28-year-old.

About Cage’s friendship with Marcel Duchamp (p. 228):

Their new friendship pleased Duchamp no less than Cage. “We’re great buddies,” he told an interviewer; “we have a spiritual empathy and a similar way of looking at things.” On many key points their aesthetic thought matched.

Cage once joined Duchamp and his wife on vacation in Spain, where the Duchamps regularly hung out with Salvador Dalí and his wife Gala:

One time at Cadaqués, Duchamp persuaded Cage to accompany him and Teeny to visit Salvador Dalí, living in a group of connected fishermen’s shacks at nearby Port Lligat. Cage disliked Dalí’s paintings, and in person disliked the painter no less. Dalí showed them a huge painting that Cage though “vulgar and miserable.” And the artist talked and talked, he said, “as though he was the king.” He found it hard to understand Duchamp’s admiration for Dalí.

I was particularly struck by this (p. 276) work with William Anastasi:

But in 1977 he came across a painter he had briefly met a decade earlier who became his lifelong chess partner—the innovative conceptual artist William Anastasi (1933–). At the time, Anastasi was seeking a narrator for his performance piece You Are, to be presented at a gallery show of his large silkscreened paintings. Allen Ginsberg and some others had turned him down. So Anastasi’s partner, Dove Bradshaw, a young artist working in clay sculpture and photography, suggested Cage.

The couple spoke with Cage at his Bank Street apartment. Anastasi explained that Cage’s role in You Are would be to report what sounds he heard in the gallery. Cage liked the idea and agreed to appear. (As he later did, telling of rubber-soled shoes, a coat button scraping the wall, someone sneezing: “do you have a cold?” he asked the sneezer; “do you need some kleenex?”)

In Listening to Art, there is no narrator.

Miskatonic University Press

Miskatonic University Press