“All of human existence has been in just a few piano keys above middle C.”

This is the text (with slides) of a talk I gave today at Everything Under the Sun: York’s Engagement in Vital Environment and Climate Change Issues, a cross-disciplinary symposium at York University: “Anthropocene Librarianship Comes in Many Forms. One is the Making of Art.” It was a really interesting day and it was wonderful to see all the different approaches and methods and disciplines fitting together. My talk was about GHG.EARTH and a powerful metaphorical implication of the sonification.

(Note 1: Thanks to my fellow librarian Tim Knight for playing the piano at the actual talk. The synth sounds here are paltry substitutes. This was my first talk to have a pianist accompanying me, but not the last.)

(Note 2: The CO₂ reading today was 404.70 ppm.)

Here is the recording of the talk, but be warned, it’s pretty poor because the air conditioner made a lot of noise.

Introduction

I’m Bill Denton, the scholarly analytics librarian in York University Libraries. I’m not a climate scientist, but I came up with a term to help me focus my thoughts on what librarians can do about climate change: anthropocene librarianship.

Anthropocene Librarianship

“The active response librarians make to the causes and effects of climate change so severe humans are creating a new geological epoch.”

The new epoch (that’s a technical term) is the Anthropocene. The details of formally declaring it haven’t happened yet but are underway at the International Geological Congress. The idea is that since 1950 or so we have had such an impact on the Earth that millions of years from now geologists will be able to look at sedimentary rocks and ice cores and say, “Aha, something big happened here.” There will be a different markers, like plastics and radioactive fallout, but most importantly for us, an unprecedented rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide. The changes that we have made to the Earth will be visible forever.

Comes in Many Forms

Anthropocene librarianship comes in many forms.

- Building collections.

- Preservation, in all forms and carriers: knowledge, culture, data, code.

- Sustainability: of buildings, practices, processes and platforms

- Preparation: for droughts, storms, floods, heat waves, higher sea levels, climate migrations, conflict.

- Disaster response: providing reference services; providing telephone and internet access; lending technology; supporting crisis mapping.

- Climate migrations: providing services for incoming migrants; preserving what they leave behind.

- Communities: hosting special shelter in cool air during heat waves, as the Toronto Public Library does.

- Advocacy.

- Information literacy and climate literacy: about the science and how is done; about the politics and how it is made; using climate change as an example subject in instruction (in science, health, business, law, engineering, social sciences, practically everywhere on campus, it works as a good example to use when talking about research methods).

- Research.

- Free and open: access, data, software, research; all work available under the best free license (e.g. Creative Commons, GPL).

- Social justice.

- Values we share with others, about preservation, conservation, stewardship and long time frames.

And finally one of those forms is the making of art. Because making art is important in all parts of life.

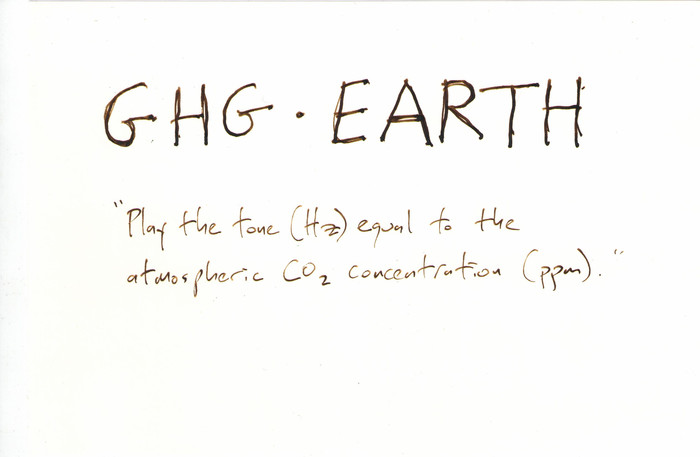

GHG.EARTH

I’m going to talk about GHG.EARTH. That’s the name of the work and it’s also a domain name—if you go ghg.earth in your browser, it will work (use Firefox or Chrome). GHG is for “greenhouse gases,” and EARTH is for “earth.”

“Play the tone (Hz) equal to the atmospheric CO₂ concentration (ppm).”

This is a musical composition, and that is the score. Let’s listen to it. Clear your head and take in the sounds. This is meant as background ambient sound, but I’d like you to place it in the foreground. It’s a little annoying and a little glitchy, but that’s what CO2 readings are like, after all. Let’s listen.

[Listen to it for a minute or so.]

That’s it. GHG.EARTH is a sonification of atmospheric CO₂ concentration meant as background ambient sound. It is a reminder of what the greenhouse gases are like today. Tomorrow, the sound will be about the same, a little different. The day after, about the same, a little up, a little down. It’s hard to hear the change from day to day because it’s microtonal. It requires attention. I’ve never been able to remember yesterday well enough to distinguish it from today, but I keep trying.

The score is very simple. There is no end specified. This web site will last as long as I can maintain it, and then I plan to pass it on to someone else. I hope it will play forever. There is no orchestration or arrangement or instrument or timbre specified. I’ll be changing the sound soon, but anyone can play this for as long as they want, however they want, anywhere.

The number, and the tone, is going to keep going up for decades. We will never see or hear it below 400 in our lifetimes.

That is the piece. For more, including links to all the source code, check the details on the web site. Now I will explain a little more about an implication of this kind of sonification.

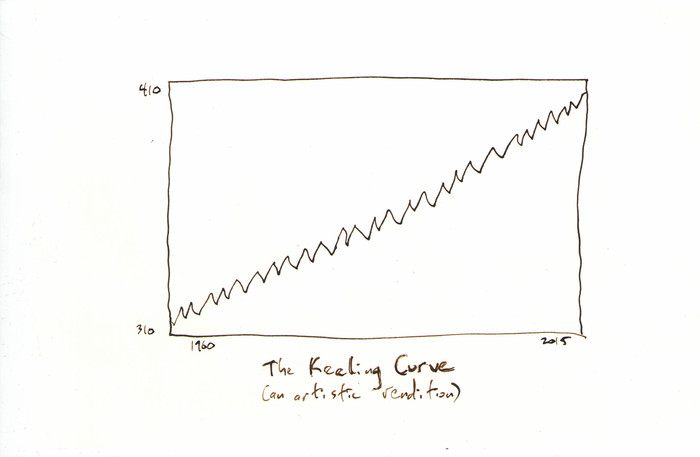

CO₂ ppm and the Keeling Curve

The CO₂ number is taken every day from the readings at Mauna Loa in Hawaii, which make up the famous Keeling Curve.

This is my artistic rendition of the Keeling Curve. You see how the CO₂ goes up and down every year, following the seasons in the northern hemisphere, where most of the land mass is. In the fall and winter leaves fall and plants die and rot, releasing CO₂, then in the summer the next year plants and trees grow and suck up carbon from the atmosphere. Meanwhile, of course, we’re always adding more and more, so every year the numbers go up and up.

Sound and hertz

That’s the atmosphere. What about the sound?

Sounds come to us as vibrations in the air, measured in hertz, which is the unit of frequency. Sixty Hz means sixty times per second.

Humans who can hear can hear something like a range of 20 to 20,000 Hz, though it varies person to person.

If you see an orchestra perform you’ll hear them tune their instruments to one note before the show begins. That’s an A (the A above middle C, in the fourth octave on a piano) and by convention it is 440 Hz.

Now, 440 is pretty close to 404, today’s atmospheric concentration. Middle C is about 260 Hz, and that’s pretty close to 280, which is the pre-industrial CO₂ concentration.

Atmospheric CO₂ concentration, when you turn those numbers into tones by changing parts per million into hertz, falls right into the middle of the piano.

Piano and scales

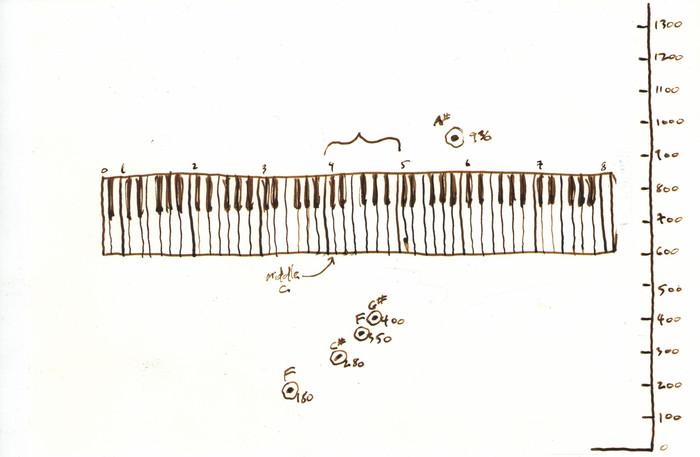

The eighty-eight keys on a piano cover just over seven octaves. There are seven full octaves and then a little bit extra at each end. A0, the lowest key, is 27.5 Hz and C8, the highest, is 4186 Hz.

I’ve marked in some important numbers and pitches here.

180 Hz is about an F below middle C, and that’s about as low as CO₂ concentrations have ever been on Earth, if I understand right. Glacial times, with ice everywhere.

280 is about a C#, the black key above middle C, the pre-industrial concentration.

350, F, is where some people think we need to get back to. You’ve probably heard of 350.org.

404 is between G and G#, just below G#, and that’s where we are now.

Looking ahead, with models, there are Representative Concentration Pathways, which a climate scientist would have to explain, but they make predictions about how much CO₂ will be in the air based on different actions we take. RCP 2.6 is a best-case scenario where emissions peak very soon, decline, and by about 2070 we’re actually removing CO₂ from the air. In that case in 2100 we’ll be at about 420, which is just over G#. Just from one side of G# to the other.

RCP 8.5 is a very bad scenario. With it, in 2100 we’re at 936 parts per million, which takes us up almost an octave to about A#.

We live in one octave

Doubling the hertz makes a tone go up an octave; halving it goes down one. With A 440, if you go up an octave, you’re at 880 Hz. Down an octave, 220 Hz. It’s an exponential scale, a geometric progression.

The CO₂ concentrations are not an arithmetic progression, changing by the same amount each year, but it’s pretty close. Right now it’s going up by about 2 or more every year. Of course, we need to lower that number, and then make it less than zero so we’re taking carbon out of the air, but we’re talking 1 or 2 or -1, not 2, 4, 8, 16.

So the two numbers, the musical and the atmospheric, are working on different scales, literally.

But that’s actually very useful: it means is that we only have one octave to live in. That fourth octave on the piano, from middle C up to B, that’s where we have to stay. Pre-industrial we were at C#. Now we’re getting close to G#. We definitely do not want to get into the next octave, which starts at about 525.

We’ve come up about seven semitones on the piano. We can go up another semitone, maybe a whole tone, but only if we’re going to come down fast after that.

All of human existence has been in just a few piano keys above middle C. Lately we’ve made an awkward clumsy melody rising quickly, uncontrolled, and the song will continue going up for years, but we need to make it go back down, back to safety, not up into the higher registers, where human society as we know it cannot continue.

That’s long term. That’s years and decades and centuries ahead. For now, day to day, GHG.EARTH is there as an ambient sonification, reminding us, telling us, every day, what the CO₂ concentration is. Listen to it, put it on in the background, quietly, and it will fade out of your attention after a while, you’ll start thinking about other things, but then it will come back, sharply, you’ll hear it again, you’ll remember what it means, and you’ll remember the situation we’re in.

I hope you find it interesting. Thank you for listening.

Miskatonic University Press

Miskatonic University Press