Elizabeth Jane Howard, the English writer, died on 2 January 2014. The obituary in the Guardian covers her life nicely and it’s a good place to start if you don’t know her.

She had an incredible life: she was born in 1923 and died aged 90 one month after a novel her readers never expected—it was her fifteenth—was published. Her mother was friends with Angela Thirkell, her mother’s father was composer Arthur Somervell. Her first husband was Peter Scott (son of Scott of the Antarctic and Lady Kennett) and her third was Kingsley Amis. While married to Peter Scott she had an affair with his half-brother Wayland Young. She had a lot of affairs, some brief and some long, usually with older married men, including Laurie Lee (on a very happy short vacation in Europe), Cecil Day-Lewis (decades later he died peacefully at the family home of her and Amis), and Arthur Koestler (required an abortion).

I was introduced to EJH by my cousin Oona Eisenstadt. It was a few years ago, when the Harry Potter books were still coming out, and she said she’d seen a letter to the editor saying the tension and excitement of waiting for the next Potter book hadn’t been seen since the delays between the Cazalet Chronicles. Oona had enjoyed the Cazalet series very much, and if Oona likes something I’ll read it, so I got the first two. I was out of town when I read them, and I remember it was a hot summer evening when I came back to Toronto on the bus soon after; the bus was about twenty minutes late and the huge bookstore near the bus station was closed by the time I got into town, so I couldn’t buy the third right away. I had to wait a day. I was annoyed.

Back then there were four books in the Cazalet series:

- The Light Years (1990)

- Marking Time (1991)

- Confusion (1993)

- Casting Off (1995)

They cover the lives of everyone in and around the extended Cazalet family from about 1937–1947, especially concentrating on life at home during the war. The Cazalets are a well off, upper middle class family who run a company that deals in imported wood. There are two grandparents who have three sons and a daughter; two of the sons are World War I veterans. Life concentrates around Home Place, the large family house in the country, where most of them move during World War II.

The Light Years has one of the most astounding, sure and confident openings I’ve ever read. Everyone in the Cazalet family is heading to Home Place for a holiday, and one by one, person by person, through the parents, grandparents, children, and servants and staff, we meet each person, seeing them get ready in the morning and prepare for the trip. The vignettes are all short, sometimes under a page, and it’s confusing at the start because we don’t know how everyone fits together, but piece by piece it all begins to sort itself out, and we figure out how this six-year-old is the child of these parents and the cousin of this girl, and finally, out of this vast sprawling canvas, it all comes together into one large extended family gathering at their special home, and we know the inner workings of every person there.

Almost twenty years after those four books came out, it was quite a surprise to find out there would be a fifth:

- All Change (2013)

There was a fine piece in the Guardian in April 2013 about EJH and the new book: Elizabeth Jane Howard: ‘I’m 90. Writing is what gets me up in the morning’.

The book came out a month before she died. It wasn’t perfect (Frances Wilson’s review in the TLS, No more Cazalet secrets, disparages it as middlebrow), but it was very good, I enjoyed it very much, and as an end of EJH’s career and life, it was an astounding achievement.

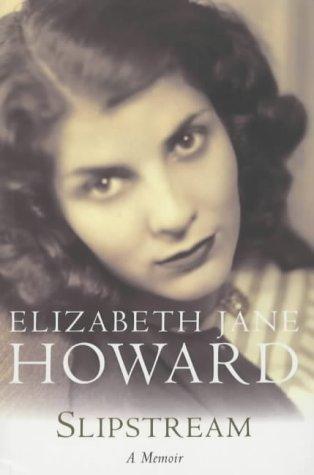

The obituaries made me want to read her 2002 memoir Slipstream, which I just finished. I’d had no idea how autobiographical the Cazalet novels were, but it turns out they’re fictionalized memoirs themselves. The three girls in the novels are all aspects of her, and other elements of other lives also come from hers. Her grandfather, like the senior Cazalet, was called the Brig, and her family all went to Home Place. Her mother was an incredibly talented but frustrated former dancer to whom everything came easily, like Villy; and like Villy and Lydia, her mother did not love her. It’s quite a surprise to read the memoir and see how much of the novels come from her life.

Anthony Thwaite’s 2 November 2002 review When will Miss Howard take off all her clothes? sums up the book nicely:

This is a brave, absorbing and vulnerable book.

It mentions some of the memorable bits from the book. Here are a few I like myself.

From the preface:

There is a sharp line between self-absorption and taking responsibility for what and who one is. Without the latter, it’s easy to assume that everything simply happens to one, and the result, an unselfish victim emerges. One needs to be on this fine line, not either side of it, and like very other endeavour in this world, this requires a good deal of practice. Speaking as a very slow learner, I feel as though I have lived most of my life in the slipstream of experience. Often I have had to repeat the same disastrous experience several times before I got the message. That is still happening. I do not write this book as a wise, mature finished person who has learned all the answers, but rather as someone who even at this late stage of seventy-nine years is still trying to change, to find things out and do a bit better with them.

Before her marriage to Peter Scott in 1942:

I spent the night before in a dingy hotel near the church with my mother. There was good deal of tension. When she asked whether I knew about the “difficult” side of marriage, I said coldly that of course I did—there was no need to talk about it. She subsided with relief.

In 1945, about conductor Malcolm Sargent:

When his chauffeur drove us back to Edwardes Square, I asked whether he’d like a drink. He said yes, and told his chauffeur to return in half an hour. I left him in the drawing room and went down to get the whisky and soda he’d asked opted for. When I returned it was to find him without his trousers. I told him anything like that was out of the question, fighting down panic with the reassuring knowledge that I wasn’t alone in the house. Unabashed, he put on his trousers again. He did hope I hadn’t misunderstood him, he said, as he left. I wondered what he meant.

In the 1970s, about her close friend Victor Stiebel, who had muscular dystrophy:

More poignantly he said on another occasion, not looking at me, “Sometimes, at night, I fall out of bed and just have to stay there until morning when Miss Brandt comes in with my tea.” I felt so paralysed, so appalled by this sudden vision of his helplessness with all the concomitant discomfort—cold, stiffness and sheer bloody frustration—that I couldn’t speak. He gave me a quick look and changed the subject. Why did I not have the kindness to say something so that he could speak of it further, as I now think he wanted to? I didn’t know then that it isn’t pity that people in such distress want, it’s understanding.

And about the death of her mother, who lived with her and Kingsley Amis for years:

“You’re a good little nurse,” she said. It was the nicest thing she’d said to me for—oh, years, and tears were hot in my eyes. I got the whiskey, served dinner, then heated some milk with Horlicks. When I took it in to her, she was dead. I picked up her small frail wrist, there was no pulse—but anyway, I knew she was dead. The knowledge that she’d died entirely alone, that I hadn’t been there to hold her hand, to comfort her, was one of the most painful experiences of my life.

It’s a powerful book. Elizabeth Jane Howard made a lot of mistakes through her life, and it took her a long time to begin to figure things out. Many of the mistakes weren’t ultimately her fault—her mother didn’t love her, her father molested her—but she took responsibility for them. They were her mistakes. Later in life she began to have greater insight into why she’d done what she’d done and why others had done what they’d done. There’s something in that for all of us.

EJH was on Desert Island Discs twice, first on 29 April 1972, when she was still married to Kingsley Amis. This exchange is worth noting:

Roy Plomley: Miss Howard, how autobiographical are your novels? How much of your own experience goes into each?

EJH: Practically none, except the places I’ve been to. I don’t write ever about people I know.

She began psychotherapy while with Amis and she found it very useful and helpful. She kept it up for years, and it must have changed her approach to writing, because future books were closely based on personal experience.

When the Cazalet series was done she was on Desert Island Discs again, on 29 October 1995. She spoke frankly about being lonely (though not as frankly as in Slipstream, where she says she’d been on her own for about fifteen years by then without any partner and without any sex life). A man wrote her some letters in response to the broadcast; she replied, and ultimately they began a relationship. He turned out to be a con man. She turned it into her 1999 novel Falling.

She was a hell of a woman. If you don’t know her work, try The Light Years and go on from there.

Further reading:

Miskatonic University Press

Miskatonic University Press