Pierre Boulez quote

It’s much too easy to rebel against everybody else, and not against oneself.

Pierre Boulez quoted from an archival recording in BBC Radio 3’s Sunday Feature episode Afterwords: Pierre Boulez at 100.

It’s much too easy to rebel against everybody else, and not against oneself.

Pierre Boulez quoted from an archival recording in BBC Radio 3’s Sunday Feature episode Afterwords: Pierre Boulez at 100.

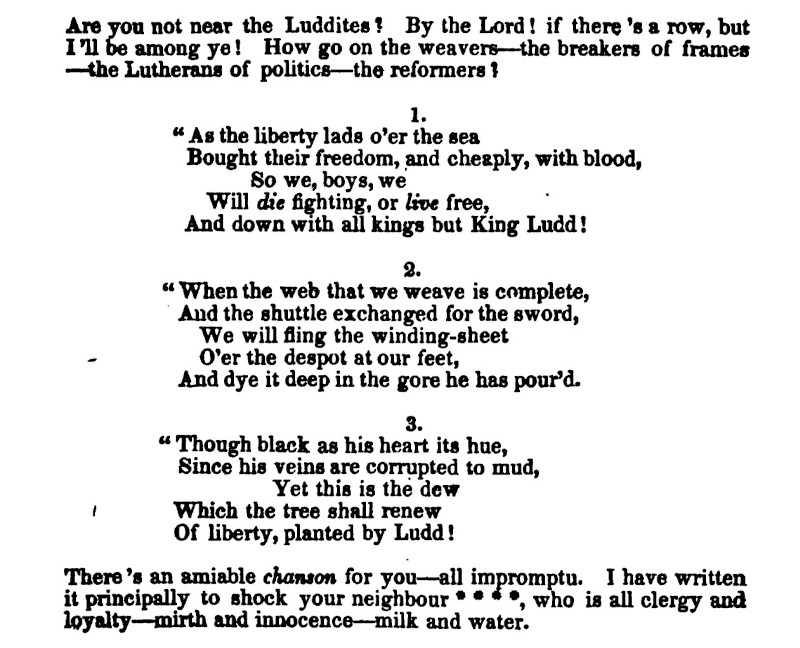

“Song for the Luddites” by Lord Byron comes from a letter he wrote to his friend Thomas Moore from Venice on 24 December 1816:

As the Liberty lads o’er the sea

Bought their freedom, and cheaply, with blood,

So we, boys, we

Will die fighting, or live free,

And down with all kings but King Ludd!When the web that we weave is complete,

And the shuttle exchanged for the sword,

We will fling the winding sheet

O’er the despot at our feet,

And dye it deep in the gore he has poured.Though black as his heart its hue,

Since his veins are corrupted to mud,

Yet this is the dew

Which the tree shall renew

Of Liberty, planted by Ludd!

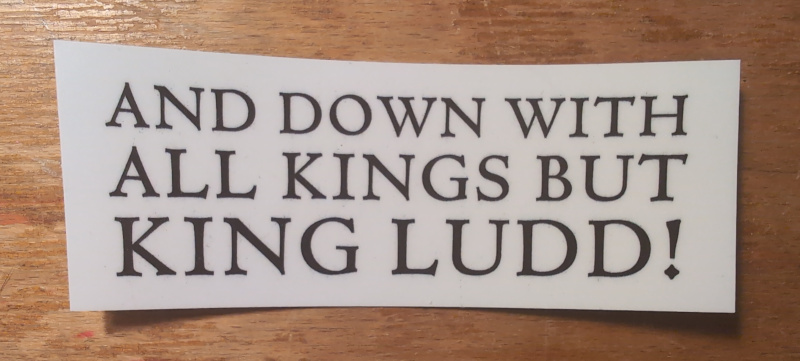

I love the last line of the first stanza, so I got the Paranoid Print Company to make a vinyl sticker of it (4 in. wide).

I have a couple of dozen to give away, so if you’re in Canada and want one, send me an address and I’ll put one in the mail.

Here it is on the page, from page 42 of volume two of Letters and Journals of Lord Byron: With Notices of His Life edited by Thomas Moore (1831):

Byron’s maiden speech in the House of Lords had been against the anti-Luddite Frame-Breaking Act of 1812. It’s on page 600 of The Works of Lord Byron Complete in One Volume at the Internet Archive.

For more about the Luddites, a good recent book is Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech (2023) by Brian Merchant.

Last week I posted this definition of art by Jerrold Northrop Moore:

Art is the imposition of form on experience.

Today I saw this in Cory Doctorow’s Pluralistic post Why I don’t like AI art:

As a working artist in his third decade of professional life, I’ve concluded that the point of art is to take a big, numinous, irreducible feeling that fills the artist’s mind, and attempt to infuse that feeling into some artistic vessel – a book, a painting, a song, a dance, a sculpture, etc – in the hopes that this work will cause a loose facsimile of that numinous, irreducible feeling to manifest in someone else’s mind.

The first half of that is basically Moore’s definition. The second half fits with Alfred North Whitehead’s longer definition, quoted in the original post.

Friday evening I saw Jürgen Geuter mention David Golumbia’s book Cyberlibertarianism: The Right-Wing Politics of Digital Technology. He said, “It is probably the most important book about tech in the last decade.” I looked it up, then checked my library; we don’t have it, so I ordered a copy. Then I checked Wikipedia, and to my surprise there was no article about Golumbia, so I started one: David Golumbia. Two other people worked on it the next day.

It’s rare to find someone like this not covered already in Wikipedia, but it does happen.

I can personally attest that Rippah Chili Oil is very good. It has tamarind in it, which gives an unusual sweet note that’s really delicious. I get the hotter version, but the mild regular version is equally flavourful. It’s good on all the foods you might expect, and a dollop on an egg works really well.

It’s only available in Toronto, but I hope the business does well and can expand. This is good stuff.

Jerrold Northrop Moore said in the episode on Sir Edward Elgar (2004) in BBC Radio Four’s Great Lives:

Art is the imposition of form on experience.

He seems to be drawing on Alfred North Whitehead, who said in 1943 (Dialogues of Alfred North Whitehead (1954)):

Art is the imposing of a pattern on experience, and our aesthetic enjoyment in recognition of the pattern.

Robert Fothergill’s Countdown Canada (1970) “is a dramatized documentary of the day when Canada becomes part of the USA” says Anna St.Onge, my archivist colleague at York University, pointing out this digitization (from York’s 16 mm print) on YouTube. It features Barbara Frum, Barry Callaghan, Larry Zolf, Abraham Rotstein and others. The catalogue record has some details, and see also the York University obituary for Fothergill.

York’s Ross Building is used as Ottawa. The Ross ramp is long gone—it was demolished in 1988 so Vari Hall could be built.

I saw The Conversation (1974) again—this time in a theatre, and it was wonderful to see it on a big screen. On the way home, I remembered an anecdote told on a talk show decades ago.

I took the minutes in this week’s meeting of the collections department at York University Libraries. This just a brief sample of what we (and all the other libraries) are trying to start to handle. It followed twenty minutes about Clarivate and how we’re not buying ebooks from ProQuest.

LCSH and the Gulf of Mexico. An executive order from Donald Trump “renaming” the Gulf of Mexico to the “Gulf of America” was met with derision and ridicule everywhere in the world outside the US, and by many inside it, but the Library of Congress quickly proposed a change to LCSH to move “Gulf of Mexico” to “Gulf of America.” There was talk around OCUL about changing how this authority record is handled, but nothing has been arranged yet. Managing it manually would be too much work for us to do alone. Thus, the change will happen here (and probably everywhere else, in Ontario and the world), and a Trump diktat will forever affect our catalogues. HC made the point that we have thousands of records using “Indians of North America” that still need to be fixed: an older and more pressing problem to solve. Bill wondered what will happen if Trump “renames” Lake Ontario to “Lake New York”—and whether the Library of Congress will exist next year.

OCUL is the Ontario Council of University Libraries, which had a Decolonizing Descriptions Working Group that issued a final report in 2022: “Recommendations in this report that refer to inaccurate, outdated and/or harmful subject headings, for example ‘Indians of North America,’ must be approached as a starting point for improving catalogue descriptions.” Today there are still over 135,000 results on a subject search on Indians of North America in our catalogue.

This is very useful: Canadian Alternatives, “A collection of Canadian alternatives to common Internet services in the spirit of the various Awesome lists.” It lists Canadian providers of online services such as web site hosting, storage, domain name management, email hosting, VPNs, and more.